There is no such thing as orchestration

The ticket booking process starts with users selecting events they’d like to attend. Once they’re happy with their selections, they proceed to checkout. Once tickets are set for checkout, the booking process locks them for a few minutes. If the process doesn’t complete within the allocated timeout, those tickets become available again. When the checkout step ends, the booking process, if needed, creates a new customer and decides how to deliver tickets based on the shipping method of choice.

In a nutshell, that’s the way, a couple of years ago, in the context of an architectural review, I was presented with requirements for a booking system.

It oozes orchestration from every pore

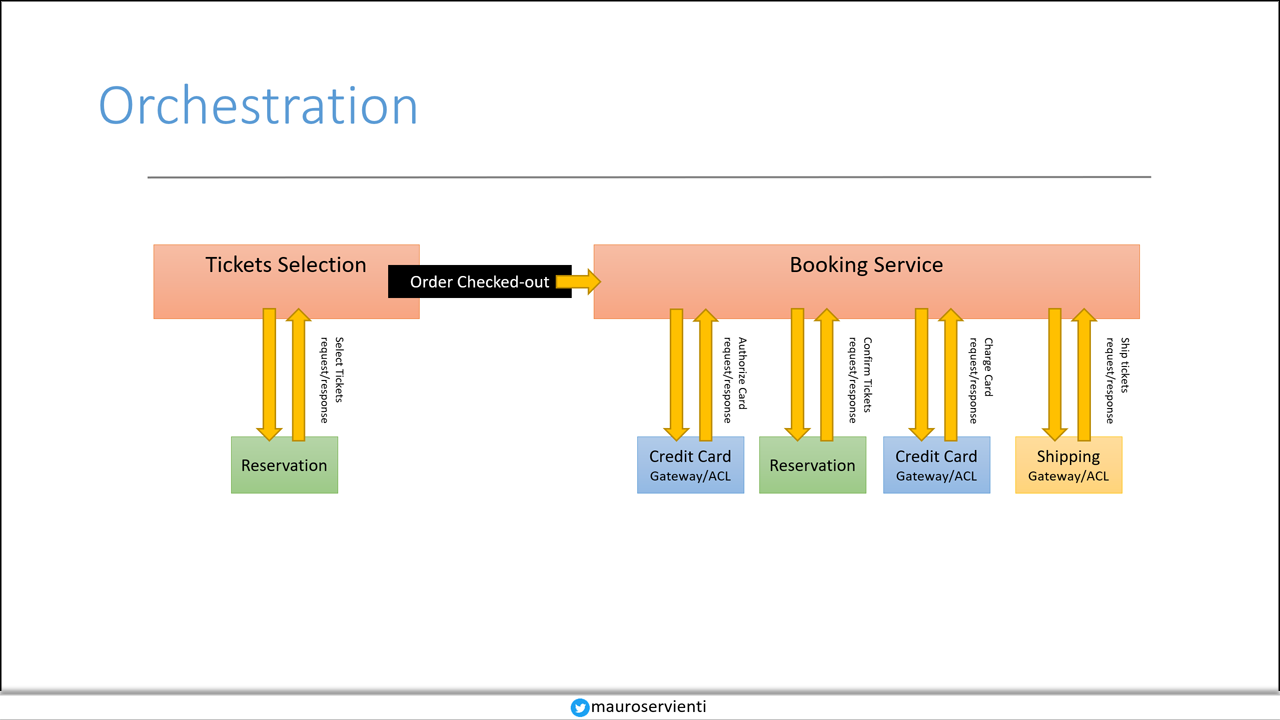

The team choice was to implement the system using an orchestration architectural style. For example, a BookingService uses commands to pilot the steps of the process across many different services, such as checkout, payments, customer management, booking, and many more. The following picture summarizes the described process:

Let me be clear. The system was alive and kicking. It had been selling tickets for the last few years (and still is) and didn’t have any significant issues. The review was in the context of some concerns the team had with recent changes they were trying to implement.

Without going into the details of the changes, the team was concerned by things like:

- to add a new payment type, they needed to change the booking service

- to change the way customers are created/handled, they needed to change the booking service

- to add groups tickets, they needed to change the booking service

And many more. Every single change they were making to the business process had to go through the booking service. The booking service was a controlling actor in the system. It was acting like a centralizing entity forcing all changes to go through it.

In other words, the booking service violates the single responsibility principle (SRP). It has too many responsibilities. Of course, one could argue that we could design a booking service composed of many classes, each with a single goal. But, even if that’s true, it doesn’t change the reality that the booking service centralizes all the duties in a single place.

Why do we think we need a booking service?

We think we need a booking service that orchestrates the process because we fall into the trap of modeling the user mental model. We model the user information and data representation instead of the behaviors that manipulate those data. Users describe the booking process in such a way that emphasizes the centrality of the booking service. Not to mention that they continuously talk about how information and data are displayed. For example, by dictating that there is the need for a dashboard showing the state of the ongoing business process. ViewModel Composition techniques can solve the dashboard dilemma.

Can we get rid of the orchestrator?

Business processes are not an orchestra; they don’t need a director. Business processes are much more like choreography; they need choreographers. Once the organization defines a process, there isn’t a need for constant directions. Instead, the process runs, and the organization monitors it instead of meticulously managing it. It’s much like a ballet; there is a training phase in which the choreographer instructs the dancers. Then, when the choreography is performed, their role is to monitor and apply tweaks and changes to fix any issues. That is in contrast with an orchestra that requires a director to keep the various players in sync.

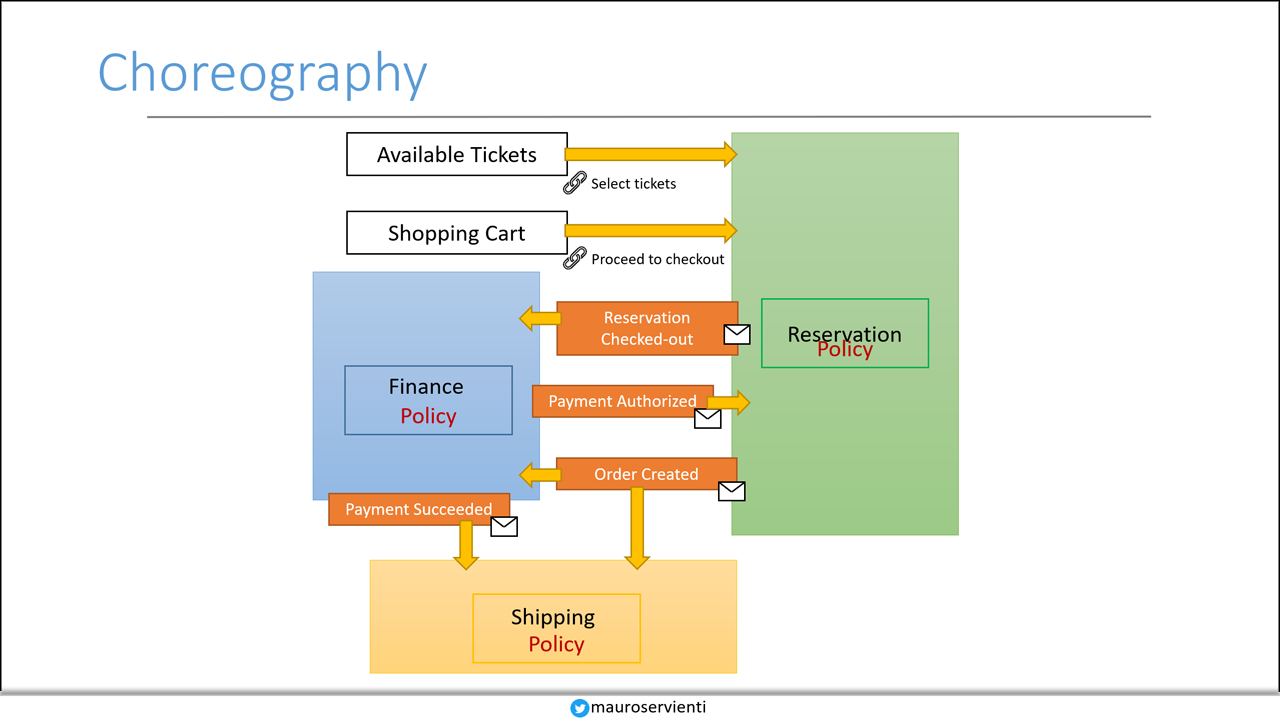

We don’t necessarily need a booking service to orchestrate the booking process. Everything starts at checkout. Once users proceed to check out, the reservation service can confirm the ticket selection. Confirmed tickets are the only requirement for payments to initiate the payment chat with the payment gateway. A successful payment closes the loop and allows the shipping part of the process to start. And so on with all the other involved services.

As in many other cases, a picture is worth a thousand words:

As you can see, the result is the same. The system will ship tickets to customers. However, the advantage is that services are autonomous. Autonomy allows for independent evolution, which guarantees the respect of the single responsibility principle. Imagine a new requirement that introduces a new payment type; it’ll only affect the payment service.

Conclusion

Coupling doesn’t only manifest itself as dependencies from a class to another one. Coupling can arise from other sources, too, like architectural and design choices. Deciding to use an orchestra director type of approach to solve a problem can result in a coupling that will reveal itself in the worst possible moment: when we need to implement new business requirements. There is nothing wrong with using an orchestrator, but it’s crucial to be aware of the limitations it brings to the table.