You want to compose emails, right?

One of the e-commerce customers just placed an order. The system needs to email an update with the recent order details and some information about invoicing and shipment.

I talked about the differences between updates, notifications, and dashboards in a recent installment: Can we predict the future?

The system is a distributed system. Different services own and store the information we need to send the email message with all the required details. For example, billing holds invoicing details, shipping delivery ones, and sales information about the order.

It’s not that different from a ViewModel/UI Composition problem, and we can solve it exactly in the same way by leveraging ViewModel Composition techniques.

For an overview of the problem and the many nuances involved, you can watch my “All our aggregates are wrong” presentation.

Let’s see in practice how something like that could work. First, let’s imagine that you’re using an email service like SendGrid, Sendinblue, or Moosend. The critical aspect is that those services primarily offer the following:

- A template engine that behaves similarly to a mail merge

- Marketing automation tools

- A promise that your messages won’t end up in the recipient’s spam folder

For the sake of what we’re discussing here, we’re mainly interested in the template engine. The mail sending service offers the ability to define one or more templates. Then, using a markup language, the template author can define placeholders that the system will fill with data at send time.

We are in charge of providing the data to fill the template. To keep things simple, let’s ignore the mass-mailing scenario. It’s just an implementation detail that doesn’t affect the solution design.

Once the customer has placed an order, the sales service publishes an event, e.g., OrderPlaced, alongside details such as the order and the customer id. Shipping and billing, as event subscribers, receive the message and react accordingly. Billing starts the card authorization process that, if successful, will result in a PaymentAuthorized event that is important for shipping to start the shipping processes (along with OrderPlaced of course).

All the mentioned services already have all the data they need to process requests and proceed with their processes. So the legit question is, how did information end up being stored in their owning services? By using decomposition techniques. I discuss decomposition options in “The fine art of dismantling” and “Safety first!”.

Once the order processing is ongoing, marketing wants to update the customer. Therefore, marketing sends emails every time there is a significant change in the order processing pipeline. For example, an accepted order is a significant change; a shipment is another critical change. On the other hand, a successful payment is not a change worth an update. However, a payment failure would be worth it.

Is there any difference between an email and a web page?

In this context, no, the only real difference is the transport we use. A web page is delivered to the user via HTTP, a mail message through SMTP. Regardless of the transport used, they are both frontends.

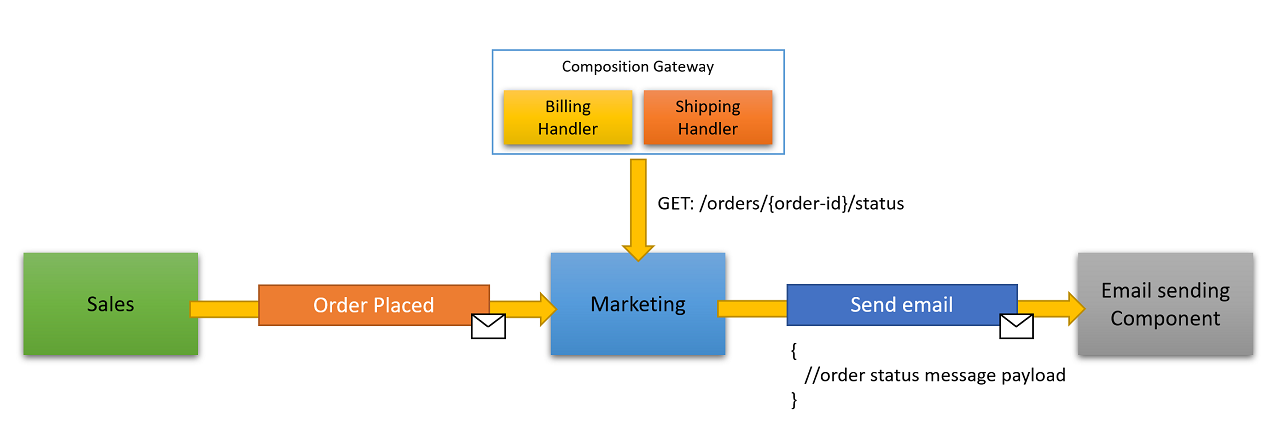

We can use the same ViewModel Composition techniques if they are both frontends. Upon receiving one of the mentioned events, Marketing invokes a Composition gateway API that will compose the required data, e.g., a JSON object, that marketing can later use to send a message to the email sender component. The following diagram shows the interactions across the different components to send the email message finally:

All this is nice and elegantly solves the problem. However, it comes with a slightly sour taste: temporal coupling.

It smells of temporal coupling

Using HTTP from marketing to invoke the components hosted by the Composition gateway makes all of them temporally coupled. If one of them is not available, we’ll fail in sending the email message. Instead, the infrastructure will retry the incoming OrderPlaced event and the mail message eventually sent. It’s a bit of a waste of resources, not to mention that the more the components, the higher the risk.

When it comes to user interfaces, the coupling is inherently there because users are already using HTTP and their requests are already synchronous. It doesn’t make sense to try to “fix” something that doesn’t need to be fixed. Email sending is asynchronous, so why do we need to accept the temporal coupling? We’ll address this in a future article. Stay tuned.

Conclusion

Composing emails poses the same set of problems of composing ViewModels for a user interface. We can approach both problems using ViewModel Composition techniques. Generally speaking, every time data leaves the system for an email, a user interface, or a report, composing information is a good solution, even if it smells a bit of temporal coupling.

Photo by Johannes Plenio on Unsplash