Can we predict the future?

Eleven years ago, Udi Dahan wrote that “race conditions don’t exist”; more recently, he gave a talk saying that commands don’t fail.

Along the same line, I wrote that “businesses don’t fail, they make mistakes”, about the fact that exceptions don’t exist. More recently, in “Tales of a reservation”, I touched on the commands don’t fail concept.

All this is nice and hopefully useful. However, it’s not enough; there’s the elephant in the room, and we’re ignoring it.

How do we deal with the user interface?

All the topics covered in the mentioned articles and videos are about the back-end part of the system. Everything, or mostly everything, can be asynchronous and, if well-designed, ignore most of the eventual consistency issues we can imagine.

That’s not the case when it comes to the user interface. A user in front of the screen is waiting for a response; we need to deal with the back-end’s asynchronous nature so we don’t feel lost.

Let me give you two examples, diametrically opposed.

First, the Amazon checkout process terminates with a screen that thanks you for your order and provides you with an order number. Then, within seconds, if not faster, an email message arrives in your inbox with the order details. At this point, I’m pretty sure that none of the order processing has happened yet. It occurred to me a couple of times that a day after having received the “order placed” email, the order was bounced back, for example, because the ordered item was out of stock, and there was no indication of when it would have been available again. Remember, commands don’t fail. If we navigate to the order details page, even if none of the processing has happened yet, we’re presented with a nice looking set of details. All those details, in my opinion, serve only a single purpose: generate confidence in customers.

Confidence leads me to the second example. Every Italian has a thing called “Tessera sanitaria” (a Healthcare card, a sort of Social Security card provided by the healthcare system). In the region where I live, that’s merged with another card, called “Tessera regionale dei servizi” (Regional services card). The Regional services card theoretically gives you access to additional services, such as document digital signing. When the pandemic was at its maximum effect at the beginning of last summer, I had to go through some Italian bureaucracy to sign some documentation. Given that most public offices were shut down, the only option was the “online” option. Unfortunately, the Regional services card needs to be activated for these additional services. To make a long story short, the process took me a little more than three months for a signing operation that lasted 5 seconds. The incompetence of the Italian public administration starts with little things like feedback to users. To enable the additional service, one needs to send an email with a bunch of documentation. Unfortunately, the email address behaves like Gargantua, the black hole from the movie Interstellar: there is zero feedback. There is no website one can go to to look up the status of their request. A month in, I got an email, obviously from a different email address, telling me that my request was incomplete. So let’s start the process again, a new email, this time to a different email address with additional documentation and no way to get any feedback. “Simple affairs complication department” is the way many Italians refer to the public administration.

We could say that the problem is that we’re leaving the user groping in the dark with no way to understand what is going on. Under the hood is the consequence of dealing badly, or not dealing at all, with eventual consistency.

In “Ehi! What’s up? Feedback to users’ requests in distributed systems” I describe the flow and the infrastructure required to provide feedback to users waiting for feedback. “Waiting for feedback” is the crucial aspect of the article. The sample mentioned above wouldn’t benefit from the described approach; in both cases, we won’t sit in front of the screen, staring at it, waiting for a status update. In the Amazon order sample, we know that it will take at least a few hours, and in the Italian public administration case it won’t happen for weeks.

Feedback patterns

By looking at the provided examples, we can try to extract some patterns.

Updates

Updates are the simplest type of feedback systems we can provide to users. In the Italian administration example, we don’t need a web portal to get information about our requests. Periodic emails or simple text messages would be more than enough. Therefore, there is no need for a dashboard. Another example of updates is support systems. When we open a support ticket, in most cases, interactions are through email, through which we get updates too.

Notifications

Notifications are helpful when we’re waiting for something to complete or to load. We’ll be sitting in front of the screen waiting for the operation to complete. If the asynchronous operation notifies us upon completion, it’s more than enough. We need neither updates nor a dashboard; we’re simply waiting for something pending to complete. In some cases, we might benefit from a tray area listing the pending tasks.

Dashboards

If we need a go-to place to get information about the status of a request or an order, like in the above Amazon case, we need a dashboard. Dashboards differ from notifications because of the possible complexity of the status updates because of all the possible status and actions users have at their disposal. A dashboard can come with notifications and updates. For example, Amazon has no notification system (at least on the website) but comes with an update mechanism alongside the orders dashboard: every time there is a significant change in status (e.g. they shipped the order), we get an email.

Persistent or volatile

Another distinction we have to make is between persistent mechanisms and volatile ones. For example, in many cases, the main difference between a dashboard and a notification/update system is that the latter can be volatile, and the former cannot. In essence, we’d expect that we can consult the order status from the web page using our laptop when ordering some goods from a mobile device. However, this is not necessarily the case with a notification system. For example, next week, we probably don’t care that yesterday at 3.16 PM, virtual machine provisioning was successful. It might even be acceptable that pending notifications get lost when refreshing the browser page or closing the app.

Architectural implications

The difference sounds trivial; however, the implementation implications are not. It’s not only a matter of technical difficulties, it’s much more a matter of architectural choices and impact on modeling.

Adding updates to a system is “easy”. It’s only a matter of knowing where to plugin the logic to understand that something worth a notification happened. In the worst case, we can hook a database trigger and apply some nasty logic to incoming insert and update requests to understand what’s going on in the system and, based on those, raise an appropriate update.

Adding notifications can be much harder. Everything I described in “Ehi! What’s up? Feedback to users’ requests in distributed systems” needs to be done. We cannot escape that level of complexity. Notifications can be categorized as updates on steroids, a much richer user experience for slightly different scenarios. There are similarities, the most important one being that both updates and notifications are a separate thing from the primary model; they are built on the side, they can be generic and used by many different services/components in the system.

Dashboards are a different beast

Let’s imagine that we’re designing an order management system, a straightforward one where orders can be accepted and later shipped. Accepting an order is a prolonged process. The sales service performs it, and the delivery department performs shipping. Due to the nature of sales in this business, incoming orders sit in a waiting line before being processed.

Now, let’s imagine that we want to build a dashboard on top of the described process. Since the order is introduced to when it’s processed, the system behavior is like the Gargantua black hole I mentioned earlier. Once the order is processed, we could publish an OrderAccepted event and build a denormalized orders dashboard view. The problem is that this “Italian public administration” style leaves users groping in the dark. The delivery department behaves similarly: no one knows anything until the shipment is shipped.

The underlying architectural and modeling problem is that the data we’d need on the dashboard are somewhere in the back-end meanderings. From the system perspective, this might not be a problem at all; in the end, what needs to be shipped will eventually be sent. It is primarily a confidence problem.

We can predict it

My dear friend Sean Farmar came up a while ago with an exciting idea that I later named “Predictive ViewModel.”

If commands don’t fail and exceptions don’t exist, we never have errors, just statuses. Most things can be modeled as state machines, or sagas if you will, incorporating errors and failures as some of their statuses.

If commands don’t fail and exceptions don’t exist, we can assume success being the most likely outcome of every request. In most cases, we can pre-calculate the resulting ViewModel at the time of the request and not necessarily at the time of the first processing outcome.

If commands don’t fail, exceptions don’t exist, and processing is asynchronous we can state that most of the models have an additional status of “accepted with pending approval,” which is not that different from an HTTP202 response that comes with the pre-calculated ViewModel.

Note: I’m talking about business errors, not technical ones. A processing error due to a technical problem will still result in an HTTP500 or a different response code to communicate various technical difficulties. I’m not saying that we must always return a 202 or a 200 and add technical error details to the response.

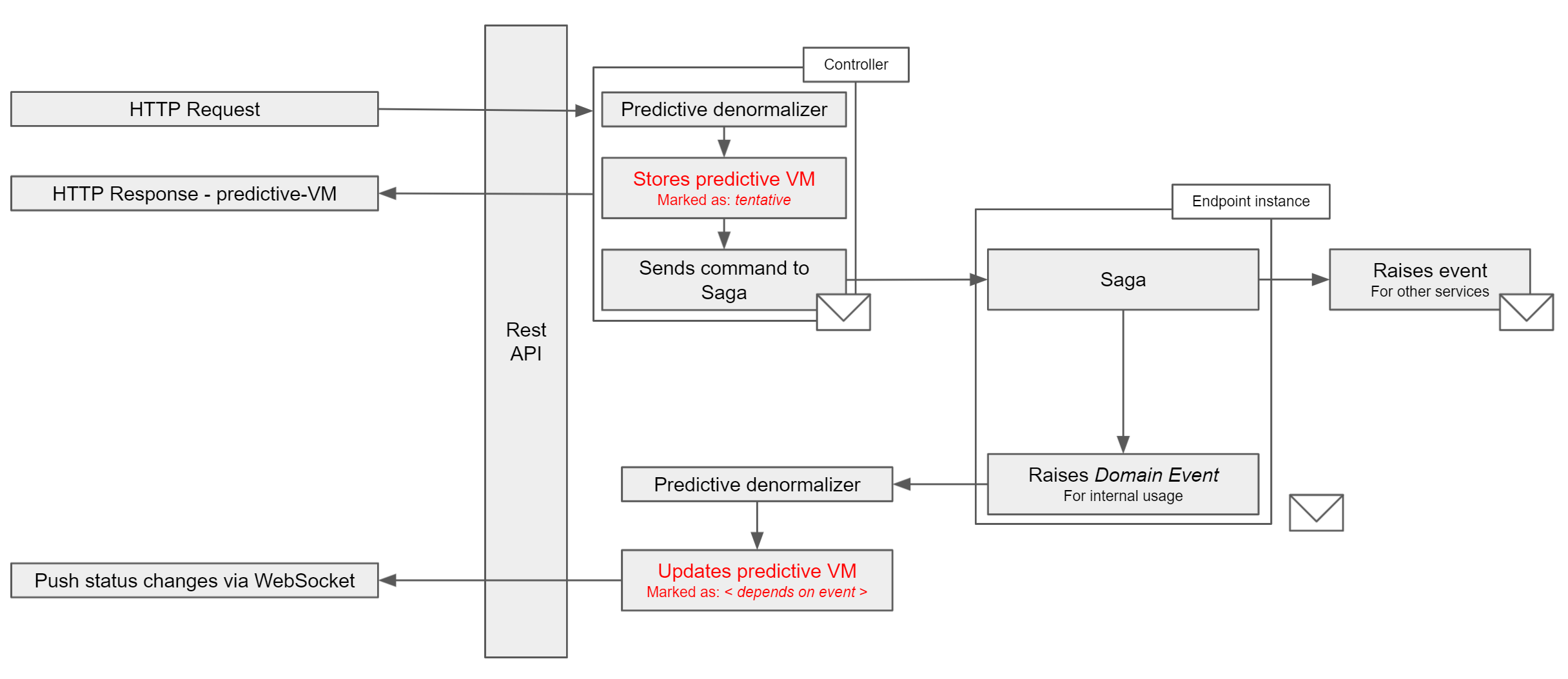

Let’s begin with a picture to recap:

Whenever a request comes in, the receiving endpoint performs two operations:

- A denormalizer takes care of building and storing the expected/predicted ViewModel; the generated ViewModel will have a

pendingstatus. - A message gets dispatched to kickoff the processing of the incoming request.

For example, processing orders is a complex matter composed of multiple event-driven sagas. The process can take hours or even days. Each saga will perform some steps and publish events that a Predictive ViewModel denormalizer will consume to update the corresponding ViewModel, for example, changing the status from pending to accepted.

The significant bit here is the first step. It’s the way we’re creating the first version of the ViewModel. It dramatically simplifies subsequent user interface interactions. We can even push a bit further and use a command-sourcing approach to storing the ViewModel. In such a way, it’ll be simpler to revert changes if, for business reasons, the request is rejected and there is a need to “rollback” changes.

Dealing with complex business rules

One could argue that all this is nice until we’re dealing with complex business rules. I could say that complex business rules resulting in complex ViewModels don’t exist. None of us is correct. Complexity exists. However, we have a tool to deal with complexity: SOA.

If we correctly identify service boundaries, and modeling behaviors and not data is of great help, we’ll end up with simpler models with clear boundaries and more straightforward business rules. And, of course, simpler models always come with simpler ViewModels.

The last bit is to bring things back together in the user interface. We already have a tool for that too; it’s ViewModel Composition.

Conclusion

Service-Oriented Architecture deals with complexity; it’s successful when the resulting design and architecture succeed in tackling the inherent complexity of the business problems we’re trying to model. However, SOA deals primarily with the back-end design, leaving some front-end questions unanswered, one being how to deal with eventual consistency at the user interface level. This article presented a potential solution to address one of the problems user interfaces have to solve when being the front-end for an SOA back-end type of system. A predictive ViewModel approach combined with asynchronous notifications and ViewModel Composition form a delicious sauce for your front-end.

Photo by Tim Mossholder on Unsplash