Own the cache!

When an HTTP client invokes a remote resource, it can use the following header to (try to) control the caching logic:

Cache-Control: max-age=<seconds>

The client request instructs the server, or any request handler in the middle, to return a cached value for the requested resource if it’s not older than the max-age provided value. Similarly, a server can instruct to not store the response in any caching layer by adding the following header:

Cache-Control: no-store

Who’s the owner?

No one. It’s by design. And it is also the beauty of the internet.

So, is it true that no one owns the resource’s cached version?

I guess the answer is two-fold. The physical ownership belongs to the caching infrastructure; for the sake of the sample, a web proxy owns the cached assets. However, the logical ownership is somewhere else. The resources belong to the server that produced them in the first place. It’s the server that can affect the lifecycle of the cached items (e.g. no-store).

At this point, it’s easy to argue that given that caches are so powerful to keep the internet up and running, we should be using caches more and more. That’s correct. However, we need to be very careful in evaluating where the cache sits in the infrastructure topology.

On the fragile relationship between ViewModels and caches

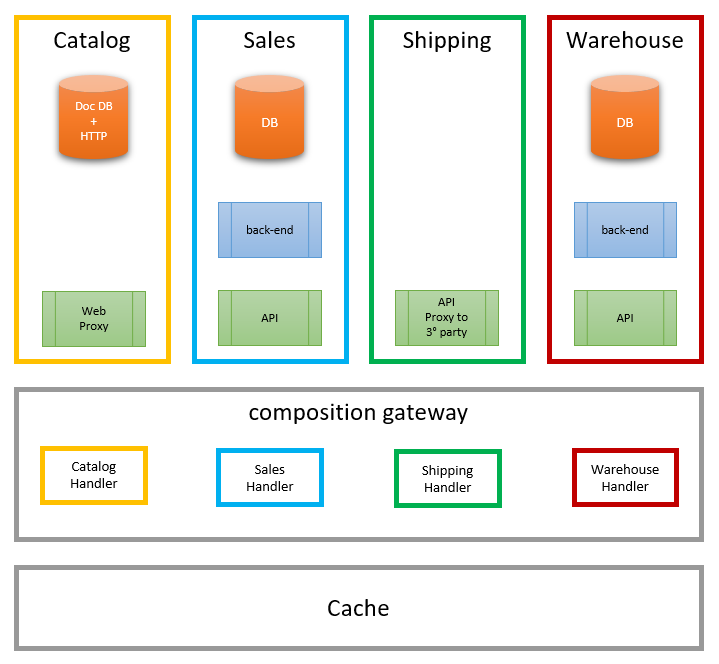

Let’s dive into the problem using a sample. Let’s imagine the requirement to design a product page whose only information is the product name and product price. The catalog service owns and stores the name of the product, and the sales service owns the product price. Both of them need to appear on the same page. We apply ViewModel composition techniques to produce the required view model and move on. The following diagram summarizes the discussed scenario:

After a while, we realize that the frontend has some performance issues while visualizing product pages. So, easy peasy, we set up a caching layer in front of the composition gateway to cache the composed view model. After that, performance gets back under control.

Prices change, but names don’t.

What appears to be a solution turns out to be a significant issue. Over time, with variable frequency, product prices change, and web pages must reflect that. However, the whole product view model is cached. Therefore, when prices change, the only option for the system is to invalidate all cached resources.

The variability in prices causes a significant issue for the catalog service, though. Whenever a price changes, the product view model cached version gets invalidated and removed from the cache. The next time that product gets requested, the system needs to hit the catalog service to retrieve what was previously cached but not changed. In essence, whenever prices change, the impact goes to the catalog service and not to the sales one. From the catalog perspective, the crucial aspect is that the effect is unexpected and, more importantly, unpredictable. The change is happening somewhere else, in sales.

Caches as a source of runtime coupling

Interestingly, the lack of ownership of the cached resources is causing issues similar to what coupling between catalog and sales would have caused. The presented caching approach couples the involved services hindering their ability to evolve. In the case of the given sample, the coupling impedes or limits the ability of sales to change prices. However, a similar issue would surface if we were to change the schema of one of the services. Suddenly, all the cached resources would have been invalid, causing even a more significant impact on innocent services—an absolute tsunami of requests due to a change in one service.

Shall we stop caching resources?

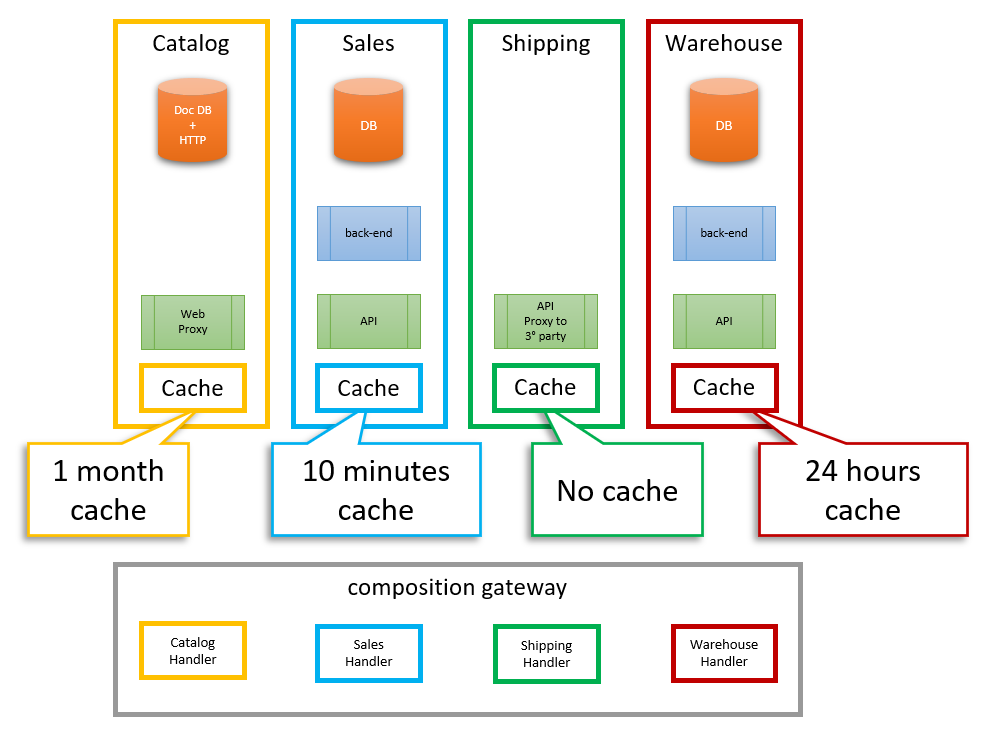

No. There is a more straightforward solution. We just need to move the caching layer inside the service boundaries. For example, the sales service needs its cache for the prices and the catalog services needs one for the product name. Sales can decide to change prices, change the schema, or randomly wipe items from the cache storage without affecting anyone else in the system. The same applies to any other service.

Given that we have ViewModel composition techniques in our tool belt, it doesn’t matter much whether the caching layer is in front of or behind the composition gateway. Having it behind does have an impact on the overall system performance, but this is negligible, especially compared to the impact of having it in front.

The following diagram summarizes the proposed solution:

One other advantage of repositioning the cache is that services can have different caching and invalidation policies. For example, the sales service can decide that product price time to live (TTL) is five minutes, and the catalog can store names for weeks. All in such a way that they don’t step on each other toes.

Conclusion

We need caches. However, we need to be careful not to blindly accept the requirement. Where the caching infrastructure is located might unpredictably impact the architecture and even the system’s runtime behavior. As in many cases when it comes to distributed systems, profoundly analyzing and understanding ownership and boundaries helps frame better solutions. If you own it, it won’t hold you.