Append-only models: The why, the when, and the how

In “All our aggregates are wrong,”, I present a distributed system architecture for a sample shopping cart.

The primary goal of the talk is to discuss coupling and its implications, especially in distributed systems.

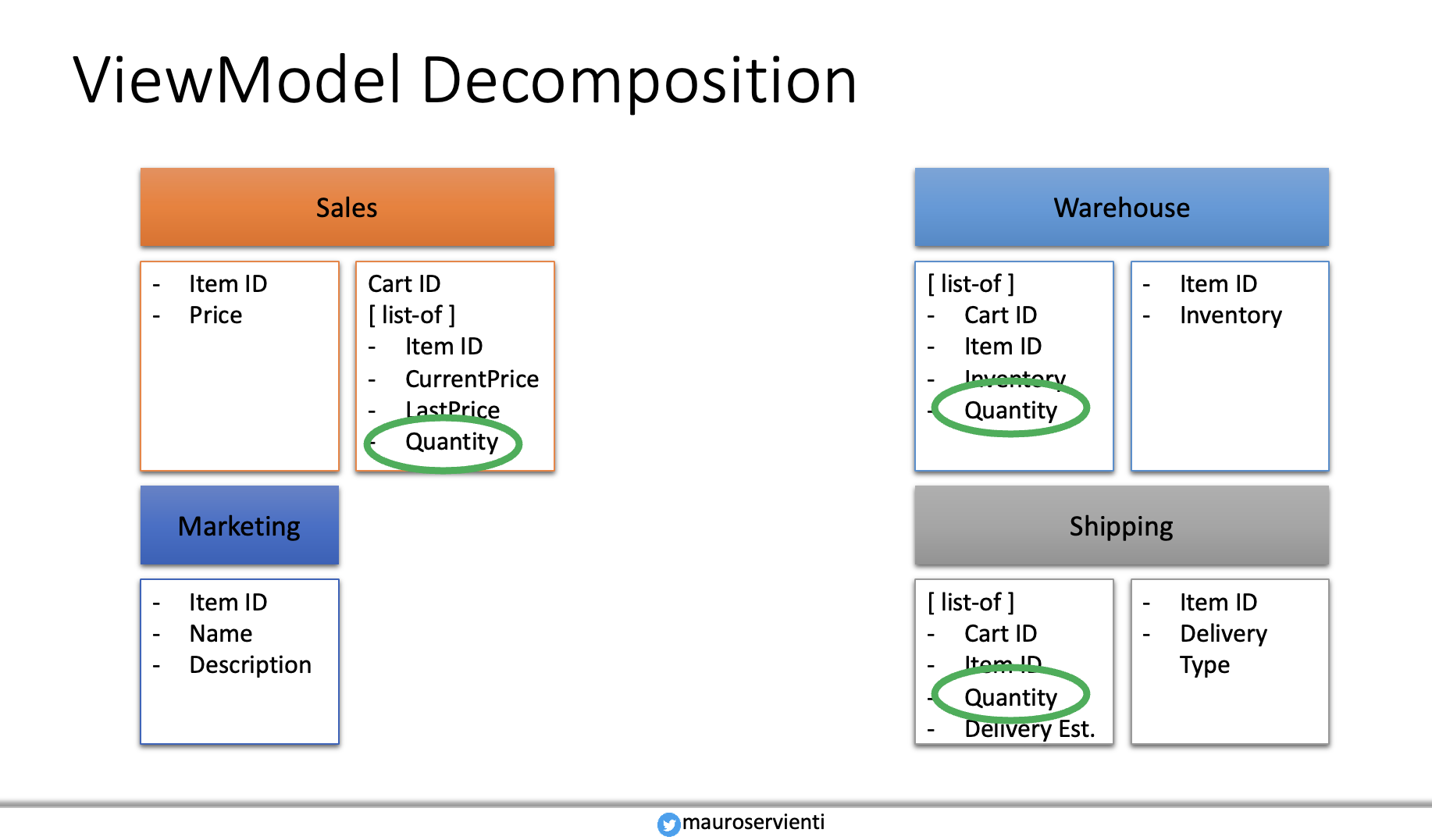

The secondary one is to present attendees with a more nuanced distributed architecture design and introduce ViewModel Composition as a solution to some of the concerns a distributed architecture poses.

During the talk, I also mentioned ViewModel Decomposition and why we might need it. In that context, I refer to append/insert-only models as the way to go when dealing with those scenarios.

Recently, Domenic shared the observation that append-only models are a rarity, and he sees updates used everywhere every day. And he’s right!

Append-only models are more complex to manage. In fact, in most cases, projections are a must-have to satisfy read requirements. That’s to say, I’m not surprised there isn’t widespread adoption. And that’s just fine; there doesn’t need to be.

Mauro, what are you talking about?

Let’s start by trying to define what append-only means. Generally speaking, an append-only model or approach is a scenario in which persisting data is never achieved using update statements but only insert ones.

A bank statement is something we have seen at least once. Banks never update statements; instead, they add data to represent money transactions or compensations.

Why would we need such a data-storing mechanism besides banks or accounting?

Let’s imagine a warehouse management system. To store data, we could use a schema like the following:

| PK | Description | Quantity | Purchase price |

|---|---|---|---|

| abc | Something | 32 | 123.00 |

If you have ever dealt with an accounting system, you probably already see the issue. One of the requirements is to run an inventory using a method like LIFO (last-in-first-out) to calculate warehouse value. I.e., we want the most recently purchased items that were added to our inventory to be the first ones out when an order comes in. Ah, crap! We don’t have any of the needed information.

The above-presented model is straightforward and answers the “How many ABCs do we have in stock” question smoothly. We cannot use it to answer any inventory-type question, like an inventory aging report. Instead, we need something more complex:

| PK | SKU | Description | Quantity | Purchase price | Purchase date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 123 | abc | Something | 32 | 123.00 | [date] |

| 567 | abc | Something | 12 | 96.00 | [date] |

| 987 | abc | Something | 1 | 157.00 | [date] |

We stop updating the single row representing a warehouse item; instead, the system inserts a new row whenever stocks are replenished. The append-only model complicates answering the “how many” question while simplifying the inventory one.

Unnecessary complexity

Now, think about a master/details relationship in a relational database where both master and details use append-only style schemas. Do you picture in your mind how complex joins could quickly become?

We can address that type of complexity through “read models” (also known as projections). In the above-presented sample, it could be a separate table that uses the first schema, where the system reverses projected data whenever the warehouse table gets a new insert. There are many different ways to achieve similar results. However, it’s important to remember that in distributed systems “read models” are a knot to untie. Things are never straightforward, oh my!

Unless strictly required, that’s unnecessary complexity we want to avoid. The first conclusion is that append-only models play nicely with only some scenarios and use cases. Use them carefully with a grain of salt.

Yeah, okay. But your sample was about items in a shopping cart

That’s right, and that is why context matters a lot. Let’s first recap the design of that shopping cart:

In the distributed system example, each service owns a shopping cart piece. Those services are autonomous and independent. Each time users manipulate the cart content, each service does whatever it needs to fulfill its request. Data end up in services through the decomposition process. But things can go wrong, and we cannot rely on distributed transactions.

More details on why that shopping cart design is an option in “All our aggregates are wrong”.

The diagram shows (highlighted in green) an interesting requirement. All services need the cart item quantity for different reasons and maybe in various formats. Sales to calculate the final price, shipping how to package goods, and so on.

If services were using an update-based model, they would have tables similar to the following:

| ItemID | Quantity |

|---|---|

| 123 | 10 |

Suppose users try to update the quantity by changing it from 10 to 12. If the decomposition process fails to communicate with the shipping service, we’re in a situation where things are misaligned. All services but shipping have the new quantity. The only way to roll back to a consistent state is for the client to remember the amount before the change and ask services to return to that value or to have some orchestration across services, but that shouldn’t exist!

Considering that the same problem could apply to many different data types, we’re making the client too stateful for reasons not pertinent. It’s also creating coupling for no good reason.

We could take advantage of the append-only model and change the shopping cart data structures in services to be something like the following:

| PK | ItemID | Quantity | RequestID |

|---|---|---|---|

| abc | 123 | 10 | [unique identifier] |

The database uses a new row to represent cart state changes whenever the client needs to operate the shopping cart. Each change is uniquely identifiable (RequestID) through a client-generated ID. If something goes wrong with any of the services, it’s enough for the client to issue a request to roll back a specific operation to restore the prior cart status. The client knows little to nothing about services schema or topology. It knows that it can undo an operation by remembering its request identifier.

Considering that the rollback request communication could fail too, it’s preferable to use messaging to favor reliability over consistency for this rollback type of behavior.

I’m sure all this might generate more and more questions. Some of them can find their way in the following articles:

Conclusion

Append-only models are a powerful way to store data. They enable system designers to implement requirements otherwise impossible. As with many things, all that glitters is not necessarily gold. They introduce complexity, and we need to weigh against the value they bring carefully.

For example, they make sense when auditing every change is required or, like in the presented example when there is the need to compensate for errors and transactions are not an option. Considering the side effects of using such a data schema is also essential. For example, querying data becomes more complex, and “read models” or projections become a must-have.

As with other architectural concepts, it’s crucial to remember that we don’t have to use them everywhere; there is no “one architecture to rule them all.” Instead, we want to select where and when to implement an append-only model precisely.

Photo by Denny Müller on Unsplash