Know your limits. Infinite scalability doesn't exist

You Are Not Google is one of my all-time favorite articles.

I wholeheartedly suggest reading it.

First, understand the problem My message isn’t new, but maybe it’s the version that speaks to you, or maybe UNPHAT(1) is memorable enough for you to apply it. If not, you might try Rich Hickey’s talk Hammock Driven Development, or the Polya book How to Solve It, or Hamming’s course The Art of Doing Science and Engineering. What we’re all imploring you to do is to think! And to actually understand the problem you are trying to solve

If you read it, you can probably skip this post. My message isn’t new either.

If you’re still not convinced or if the last paragraph doesn’t speak to you, let me try it from a different angle.

My first job was in an accounting department. Windows was version 3.1, and Office was version 4.5. And no one was aware of the Millenium bug. Yeah, I’m old. Someone prefers to say experienced. Maybe I’m experienced too.

Computers were still a new thing for the organization. When I joined, the central theme was transitioning the organization from a traditional corporate accounting process to one based on accounting by order. Being a manufacturing company, I was deeply involved with the whole manufacturing process starting from warehouse and fulfillment.

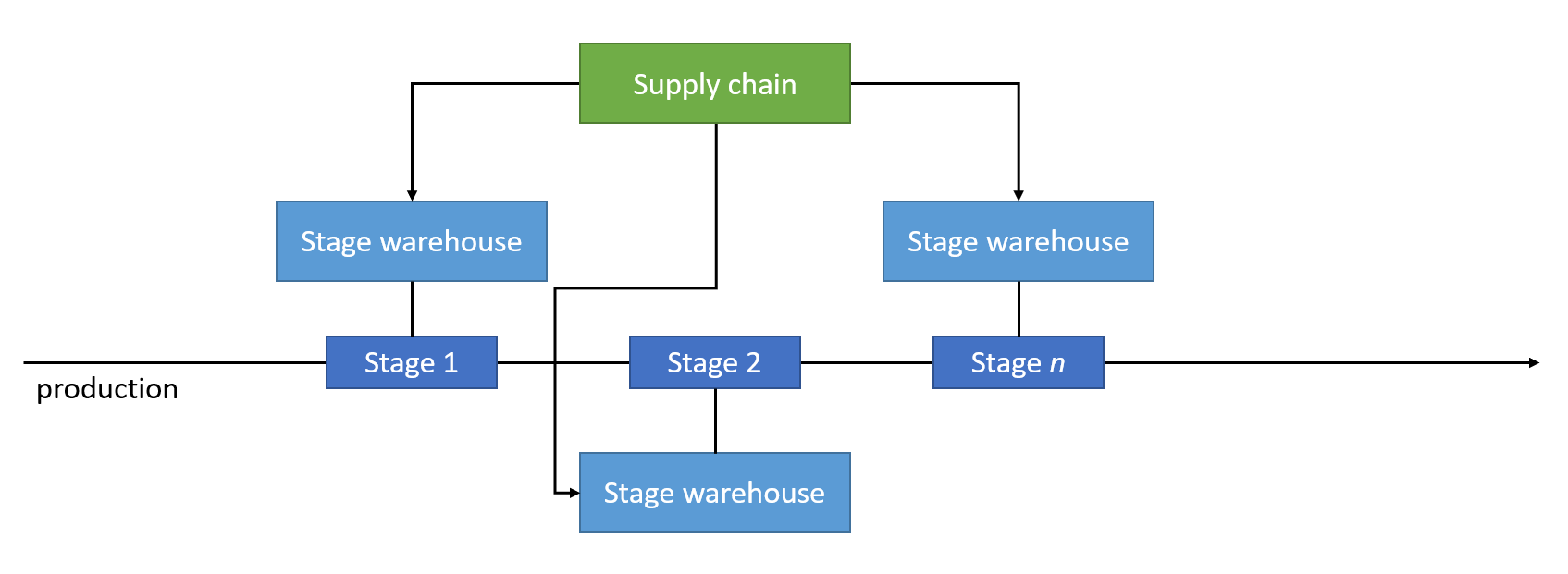

The organization was far from being significant. And as such, the warehouse wasn’t massive. At the time, I got fascinated by the logistics processes in place to support production. The warehouse was “distributed,” and each station on the production line had its warehouse. That meant people working at a specific manufacturing stage were responsible for their portion of the warehouse.

Looking at that setup, with today’s eyes, is enlighting. It was a small distributed system. Each manufacturing stage was autonomous in managing the daily warehouse tasks. They were not responsible for fulfillment, though. That was centralized.

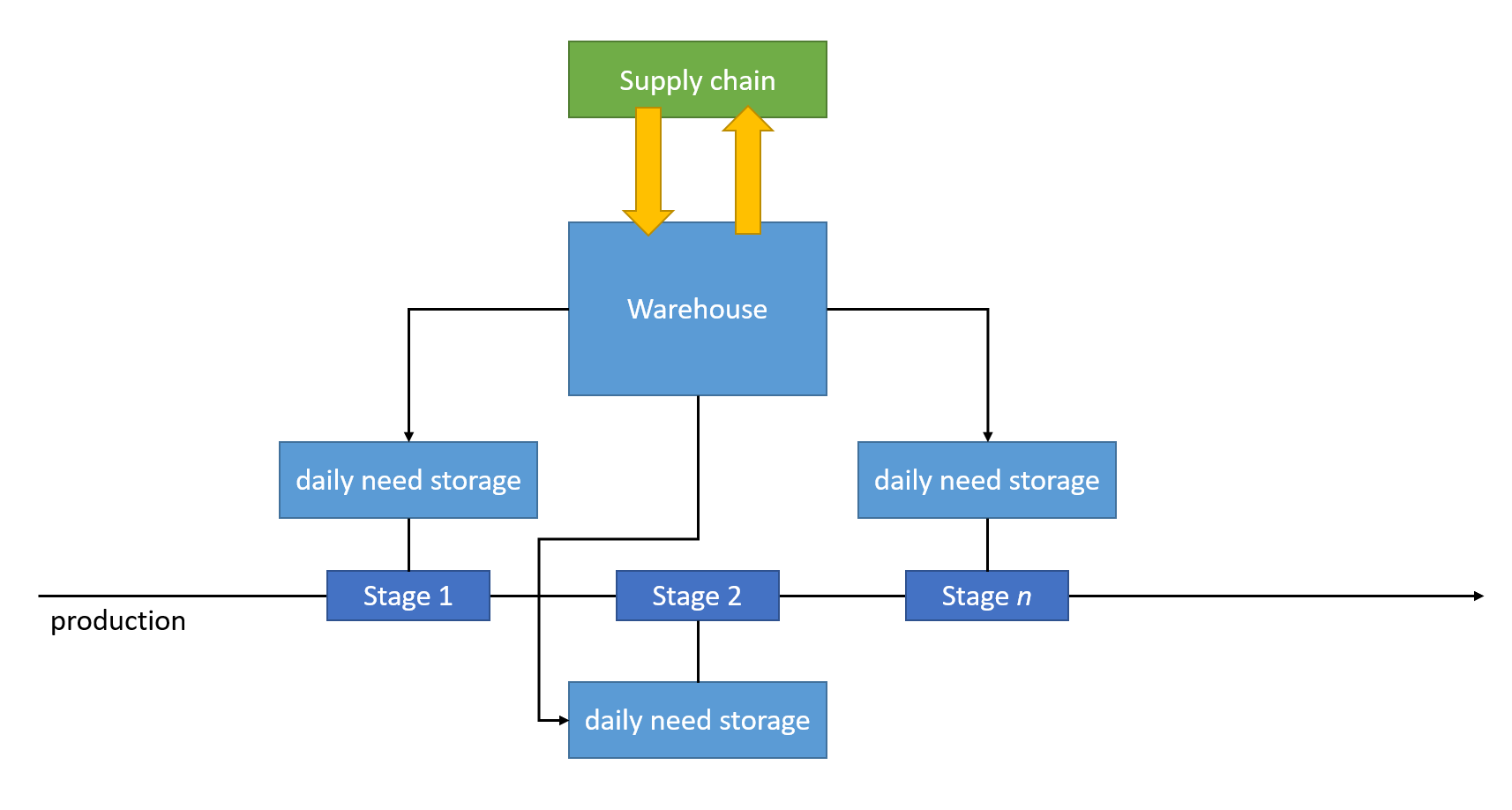

The organization grew and moved to a new larger plant. Warehouse management was rebuilt from the ground up. With more than one production line, having only distributed warehouses was not sustainable anymore. The warehouse design changed to be a mix of centralized and distributed. Connectivity between the not-anymore autonomous manufacturing stations and the centralized, automated warehouse was implemented.

The following synthetic diagrams summarize the before and after warehouse management architecture:

The two designs, theoretically, are interchangeable. However, if we swap the approaches, the result is suboptimal. The first doesn’t scale up, and the latter doesn’t scale down.

For the first design to scale up, we have to assume all instances of the production line work the same way. It is unlikely and will result in a requirement to rebalance station-bound warehouses. The second has the opposite problem. It’ll cause a chatty warehouse management system that is not worth it if used on a single production line.

Let me reiterate that. The first would be suboptimal when used with more than one production line. The second would be over-engineered for a single production line. Change, even if radical, is a necessary step when evolving or scaling.

We need microservices

No, we don’t.

We all probably agree with the presented warehouse design choices, but we don’t apply the same logic to software design in many cases. I’m not sure what’s the root cause. I have a few hunches, though.

Hype

I understand nothing about wine. Give me a one Euro wine bottle, and I feel it’s terrible. However, I have no way to distinguish between wines that are thirty euros or fifty euros. I’ll probably jump on the hype train. If everyone says that the fifty euro one is better, I’d agree.

Everyone can’t be wrong, right?

The same goes with big data, microservices, or containers, to name a few. If everybody says they are good, they must be, and moreover, they must be the solution to all my problems.

That is how it starts. Instead of looking at the business problem, we let the technical hype or cool new kid on the block take over.

Intangibles come for free

I also believe that human beings can estimate the value of tangibles relatively quickly, but not so much the intangibles. For example, when presented with the cost of a building, we can see the dollar value. When presented with the “cost” of time, we struggle to make the connection. It’s trivially easy to observe people investing a tremendous amount of time addressing issues with a low or negative return on the investment (ROI).

A few years ago, an acquaintance drove 300 kilometers to save a few bucks on a new phone.

I observed this effect in two different settings in the last twenty years.

Due to our inability to estimate intangibles, we tend to underestimate the cost of changing when there is no perception of physical change. That manifests itself with the famous last words, “how long could it take?” or “how hard can it be?” A typical example in the software engineering world is the decision to upgrade a dependency to its latest release, even if we’re aware of the many breaking changes and there is no compelling reason. I witnessed teams moving from Entity Framework to Entity Framework Core, assuming it was still Entity Framework, even if the project didn’t benefit from the upgrade.

The presented behavior, to some extent, is supported by customers or users. How often have we heard statements like “for you, it’s certainly easy”? The assumption here is that software is a toy we play with, and everything is easy. It’s another form of the “intangibles come for free” mindset.

We can design for changes

We have a crystal ball. We know what the system scalability requirements will look like in three years, and we’ll shape today’s architecture to accommodate the future. Sure, you bet!

How often have you prematurely designed an extension point that later turned out to be completely useless? I did it many times. Those are instances of over-engineering the design, assuming we can accommodate future changes even if we have no idea what they’ll be.

That’s where the myth of infinite scalability is rooted.

About knowing your bounds

You just got out of college, and you’re looking for your first car. Would you buy a seven-seat car because maybe you’ll have a seven-person family and a dog in ten years or would you go with a small used one because you have no idea where you will be next month?

And even if you’re sure you’ll have a large family, does it make sense to buy today something that will be obsolete before you genuinely need it? Not to mention that the family might be eight people.

Predicting the future is hard. Investing money (effort, resources, and time) in designing solutions to accommodate the unknown is a waste. Rarely will those solutions fit future needs, and when they do, it’s often by chance.

Does it mean that the only option is to design for what we know today? Not necessarily. We have to define today’s requirements and future limits clearly. Knowing what today’s design can achieve is crucial to understanding when it’s time to change.

Let me give you one more example. Let’s say we’re designing a website. Nothing fancy. A critical question is how many concurrent requests do we need to be able to sustain? Let’s imagine 25k visitors/day and, for the sake of the discussion, that each visitor visits six pages. That means 125k pages/day. If traffic is concentrated over 11 hours a day, it’s 12k pages/hour, which turns into a miserable 3.3 pages/sec.

Probably the cheapest cloud virtual machine can sustain that load—no need for fancy architecture or strange and complex deployment solutions.

Where are we going?

The next question should be: what’s the forecast? Similar to when we leave for a trip and need a destination. When designing a system, we need to know what type of load the system must be able to sustain. For example, 25k visitors a day might lead to different architectural choices depending on how they are concentrated: If all of them visit the website once a day in a short timeframe, we design things differently than if they were distributed over 24 hours.

Once we have a well-defined destination, we should ask a follow-up question: does the “destination” apply to the whole system or only to a subset?

In other words, imagining that the scalability requirements will move from 25k visitors a day to 100k, how and where will those 75k more visitors impact the system? Will they quadruple the read requests, or will they impact writes too? Will those new requests distribute equally to the whole system, or will some areas be affected more than others? Will they distribute uniformly over time, or will there be unexpected peaks in traffic?

Understanding how the load affects the system behaviors is vital to learning where we should apply changes.

How do we go about understanding it is a legitimate question. The answer is pretty straightforward: by measuring. We want to have all sorts of metrics to capture data that we can later use to generate insights to present to decision-makers.

Testing

There is one last outstanding question: How do we know that the system will behave correctly under the forecasted load? And it’s not only that. How do we know that the metrics we have in place will provide the information we expect when we need them?

To some extent, it’s not that different from a disaster recovery process. We hope never to need it, but we must be sure that it’ll work if required.

Testing is the answer to both questions. Specifically: load testing. What we want are load test scenarios aiming at providing the following sets of data:

- Under known real production scenarios, is the system behaving as expected?

- Under forecasted future production load, are the metrics in place raising the bells we expect to hear?

- Under unexpected production load, are the metrics in place providing enough data to understand what’s going on?

There is one crucial aspect worth mentioning. All test patterns must be realistic scenarios. There is no point in hammering a product page with unrealistic test cases. It might give us information about what could happen in a DoS kind of scenario, but it’s not useful for what we are looking for in this case.

Conclusion

Infinite scalability was a myth, and a myth remains. I’m sorry about that. The faster we get over it, the quicker we’ll start looking at our architectures for what they are: a disposable thing that will be redesigned when requirements change significantly. As we’ve shown, we want to build and use tools to help us identify those significant changes and gather the data we need to make the best next step.

Photo by Ivan Slade on Unsplash