Is it complex? Break it down!

Over time, I learned how important words are. We have absolute concepts like color; something is red, yellow, or green. And then we have no such absolute concepts as weight, size, or complexity. When we say something is small or micro, it’s always compared to something else. The same goes for weight or complexity. Something is not heavy; it’s heavier or lighter than something else. On the same line, one thing is more complex than another thing.

People often describe some technology or architectural style as heavy or complex. I’m guilty, too; I’ve done the same things many times.

But are they complex or heavy?

Let me use NServiceBus sagas as an example. I like to describe sagas as a modeling tool. We use sagas to model long-running business processes or transactions.

The usual disclaimer applies: I work for Particular Software, the makers of NServiceBus.

Let’s consider the following business process:

At checkout, the system converts a shopping cart into an order. Once converted, the process proceeds to fulfill and prepare the order for shipment. When the order is shipped, an invoice is issued and marked as due based on its payment terms. Later, the order management system checks for overdue invoices.

In theory, we can have a ginormous saga handling everything I’ve described.

If we do that, we’ll have a complex implementation of what appears to be a complex business process. And every time we have to tweak it to adapt to change requests or deploy it, we’ll perceive it as heavy.

I’m using complex and heavy because we can implement the described business process in a simpler, less complicated, and thus lightweight way.

It’s not a technical issue

As in many cases, it turns out that what makes the implementation complex and heavy is not the technology of choice but the analysis and translation of the business process into architecture.

If we slavishly translate the business process into code, it’s not surprising that the outcome can be heavy or complex. I believe it’s because we trust the user mental model too much. Instead, we should first break up each business process into its founding procedures. After that, we should start modeling the technical solution, for example, using sagas as a modeling tool.

Let’s break it apart, first

the system, at checkout, converts a shipping cart into an order.

The first step is to move all items, primary keys, from the shopping cart to a new entity, the order. And delete the cart content. Those are two operations, for example:

- a post request to initiate the checkout and create the order entity

- an event, a message on a queue, to broadcast the order creation that we can use to empty the shopping cart asynchronously.

Asynchronously, because if we’re building a distributed system, the shopping cart doesn’t exist. The only way to reliably empty the cart is by allowing each participant service to asynchronously decide how to deal with order creation and the need to clear it.

Is the order entity a long-running business transaction?

At this point, a good question is whether the order entity represents a long-running transaction. The way the requirements describe it suggests that it does, but I bet it doesn’t. The order entity is nothing more than a primary key, an ID, and maybe a few attributes, such as the creation date.

Don’t be tempted by the user interface needs. We need to display an order summary page with all the order details. That’s not a good reason to have a rich-order entity with all the details. ViewModel Composition techniques solve the read model problem. For more information: Read models, a knot to untie.

Next, please

Once converted, the process proceeds to fulfill and prepare the order for shipment.

If a service in the system already broadcasts an event to notify that an order has been created, the warehouse, another service, can react and proceed with order fulfillment. Similarly, shipping can.

From a service boundaries perspective, fulfillment and shipping are not part of the order management “thing” because the order management thing does not exist. Order management is a “user mental model” concept that doesn’t translate into a service.

Fulfillment and shipping are long-running business transactions, though. They are both started by the order-created event. During its lifecycle, fulfillment will collect items from warehouse shelves and take care of all the exceptions connected to no more in-stock items. It’ll do so by raising events, not directly managing the exception. Other services will handle those events and make decisions on how to proceed. One of these might be shipping, which can turn what was supposed to be a single shipment into multiple deliveries once stocks are replenished.

Shipping is a long-running business process, too

Like fulfillment, shipping starts with the order-created event and reacts to interesting events broadcasted by other services. For example, a fulfillment-completed event might trigger the final steps to deliver the order to the customer.

When the order is shipped, an invoice is issued and marked as due based on its payment terms. Later on, the order management system checks for overdue invoices.

All that said applies to finance, too. Finance reacts to the order-shipped event, broadcasted by shipping, and issues the required invoice. Invoicing implies charging the user’s credit card, which requires authorizing the card first.

Surprise, surprise, finance is a long-running process too

We can create a separate saga, or more than one, to handle the payment and invoicing procedures. Payment is a different saga than the one needed to generate the invoice. But it doesn’t end here. Once the invoice is issued, which turns to be an event published by finance, a third saga is kicked off to keep track of the shipment-returned event to refund the user’s credit card eventually. Another option could be if the system allows different payment methods: if customers could buy and pay, upon receiving the goods, using a wire transfer, the system needs to keep track of overdue payments.

A sample implementation of this last bit is described in my Got the time article. If you’re interested in a sample that covers the whole presented scenario, just leave a comment below.

Conclusion

When looking at long-running business processes, it’s easy to be overwhelmed by the apparent complexity. In many cases, they are not that complex. It’s the way we frame them that creates complexity. Beware that the user’s mental model can be a traitor. We must spend time dissecting processes to break them down into their founding components. Once that’s done, each part is more straightforward and ready to be implemented. Many of these simpler parts can still be long-running processes. If that’s the case, sagas are an excellent solution.

As in many contexts, It’s the single responsibility principle, baby.

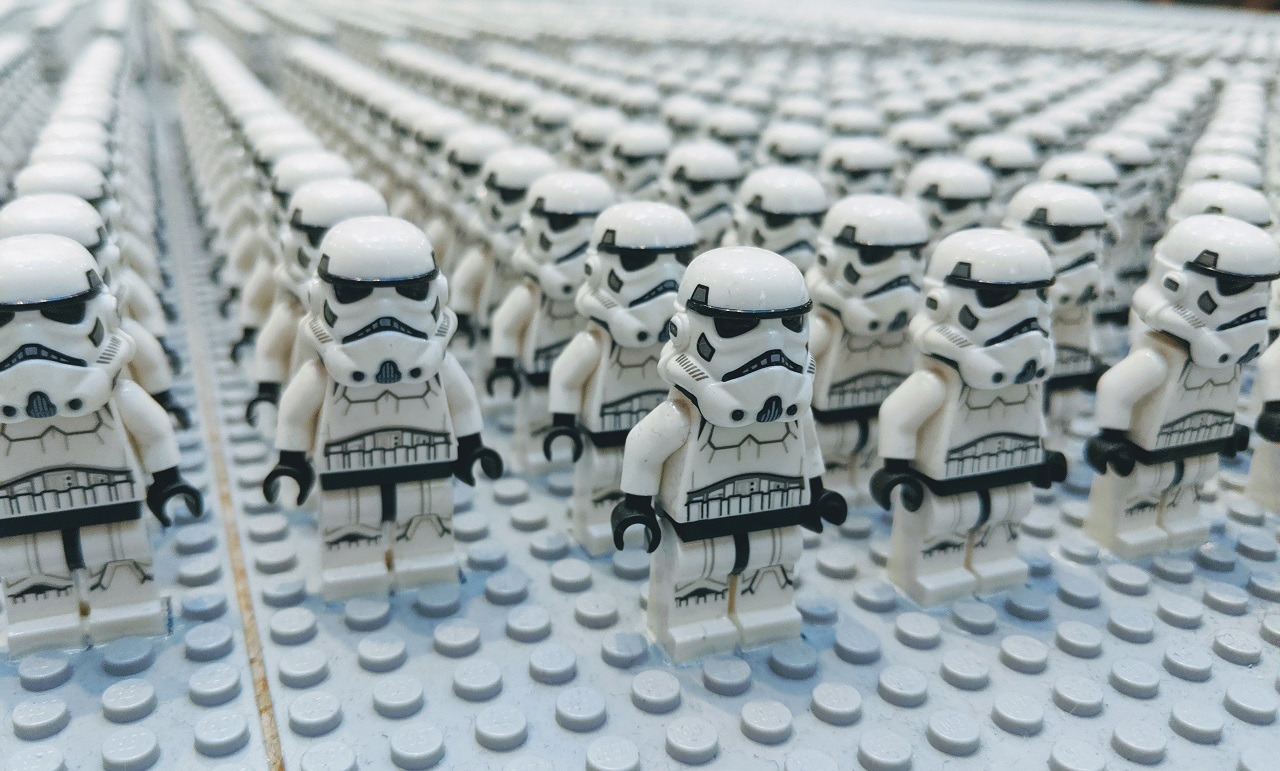

Photo by Omar Flores on Unsplash